Economists talk about rivalrous and non-rivalrous goods, but Culture is neither rivalrous, nor non-rivalrous; it is anti-rivalrous.

I. Rivalrous

Rivalrous goods diminish in value the more they are used. For example, a bicycle: if I use it, it gets me from here to there, if you use it, it gets me nowhere. If I acquire your bicycle, you don’t have it any more. Only one of us can have the bicycle at one time. We can share it to a limited extent, but the more it’s used the less it’s worth; it gets dinged up and wears out. The more people use the bicycle, the less utility it has.

All material things – things made of atoms – are rivalrous, because an object cannot be in two places at the same time. Everything in the physical world is rivalrous, even if it’s abundant.

A commons is a rivalrous good. Hence the “tragedy of the commons“: the more people use a square of land, the less valuable it is to each of them. The grass gets eaten too fast to grow back, the soil can’t handle the incoming rate of sheep shit, and degradation ensues.

Rivalrous and non-rivalrous are often confused with scarce and abundant, but they’re not the same thing. Air is abundant, but it is still rivalrous – some “users” could make it toxic for the rest of us, because air is not infinite. Land and water are so abundant in North America that Native Americans couldn’t imagine owning or depleting them, and look what happened. We treat the oceans as infinite, but they are not; human pollution and exploitation is killing ocean life. We also pollute the vast ocean of air – hence acid rain. Air and oceans are commons.

Commons are commonly-held rivalrous goods. Because they are rivalrous, some uses (or over-use) can poison them or otherwise diminish their value. For that reason, Commons(es) actually merit rules and regulations.

But Culture is not a commons, because Culture is not rivalrous and can’t be owned.

II. Non-Rivalrous

Non-rivalrous goods, as their name implies, don’t diminish in value the more they are used. A favorite example of a non-rivalrous good is the light from a lighthouse. It shines for everyone. No matter how much you look at it, I can see it too.

This is a pretty good example, but it’s not quite right. Theoretically, if enough tall boats are in the harbor, they actually can crowd out your lighthouse light.

Consider sunlight in Manhattan; yes, the sun shines for everyone, but if they build a high-rise next to your apartment you won’t see it any more. There’s only so much sunlight that hits a certain area, and that light is rivalrous. You can always move, of course – except land, while abundant, is definitely rivalrous and not infinite, so you’ll have to engage in some rivalry to do so.

The light metaphor has another problem: is light a particle, or a wave? If it’s a particle, then light is rivalrous. If it’s a wave, then it’s not.

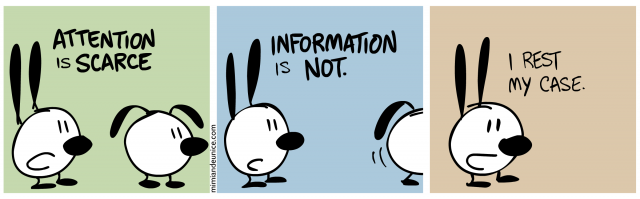

Thomas Jefferson used the example of candle fire, writing “He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me.” Of course candles burn out but it’s not the light that’s diminished, it’s the candle. That’s a great metaphor for attention, which is scarce: once our attention is used up, the light goes out.

Thomas Jefferson used the example of candle fire, writing “He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me.” Of course candles burn out but it’s not the light that’s diminished, it’s the candle. That’s a great metaphor for attention, which is scarce: once our attention is used up, the light goes out.

But Culture is not non-rivalrous either.

But Culture is not non-rivalrous either.

III. Anti-Rivalrous

Anti-rivalrous goods increase in value the more they are used. For example: language. A language isn’t much use to me if I can’t speak it with someone else. You need at least two people to communicate with language. The more people who use the language, the more value it has.

Which language do you think more people would pay to learn?

- English

- Esperanto

- Latvian

More people spend money and time learning English, simply because so many people already speak English.

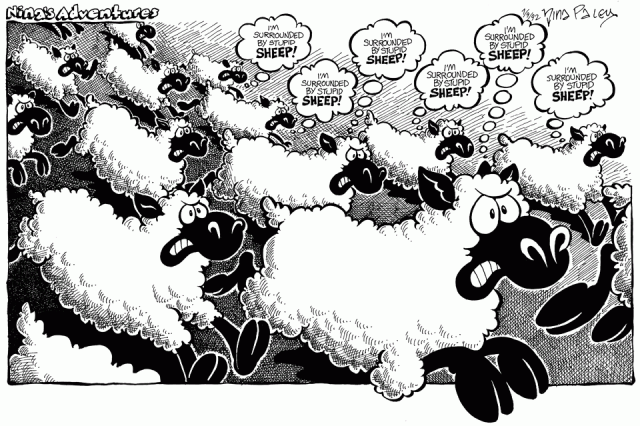

Social networking platforms increase in value when more people use them. I use Facebook not because I love Facebook (I certainly don’t), but because everyone else uses Facebook. I just joined Google+, and will use that instead of Facebook if enough other people use it. If enough people flock to yet another platform, I’ll use that instead. Meanwhile I love Diaspora in principle (I was an early Kickstarter backer, before they surpassed their initial $ goal), but I don’t use it, because not enough other people do. When it comes to social networks, I am a sheep.

Culture is anti-rivalrous. The more people know and sing a song, the more cultural value it has. The more people watch my film Sita Sings the Blues, or read my comic strip Mimi & Eunice, the happier I’ll be, so please go do that now and then come back and read the rest of this paragraph. The more people know a movie or TV show, the more cultural value it has. Monty Python references attest to the cultural value of Monty Python – we even use the word “spam” because of it. Shakespeare‘s works are culturally valuable, and phrases from them live on in the language even apart from the plays (“I think she doth protest to much,” etc.). The more people refer to Monty Python and Shakespeare, the more you just gotta see em, amiright? Or not, it doesn’t matter whether you see them, you’re already speaking them. That all culture is a kind of language, I’ll leave for another discussion.

Cultural works increase in value the more people use them. That’s not rivalrous, or non-rivalrous; that’s anti-rivalrous.

IV. Some Exceptions That Prove The rule

I know what you’re gonna say now: “what about my credit card number? That doesn’t increase in value if it’s shared!!” That’s right, Einstein, because your credit card number is not culture. Here are two things that aren’t made of atoms and are nonetheless rivalrous:

1. Identity

2. Secrets

Identity is some mysterious mindfuck that my very smart friend Joe Futrelle says no one has satisfactorily defined yet. But whatever identity is, it’s rivalrous. If more people were named Nina Paley and had my home address and social security number, I’d be screwed. But that should highlight that my name, home address, and social security number aren’t culture. They may be information, but they’re not culture. They don’t increase in value the more they are used.

Secrets have power as long as they’re secrets. They lose their power when they are shared. When I become conscious of some secret that’s weighing on me, I share it with at least one other person (even if they are a confidante also sworn to secrecy): I can feel the secret’s power diffused just by the act of sharing. Notice I use “power” here instead of “value.” Secrets may be of little or no cultural value – most people don’t really care who that guy slept with 6 years ago – but they can certainly have power, especially when used for blackmail. Which is why it’s important they remain secrets, so they’re not used for blackmail, or harassment, or any reason at all. Privacy is important. Because secrets aren’t culture. Culture is public. Secrets are, well, secret. Until they’re public, whereupon we get scandalous stories that are culture – humans love to gossip – but aren’t secrets any more. The story might gain value, but the secret loses it.

Money vs. Currency

And how about money? Money is scarce, right? It has to be, or it doesn’t work (thanks Wall Street & Federal Reserve for screwing that up). But currency has more value the more it is used! Would you rather have your scarce 100 Euros in Euros, or in giant immoveable donut-like stones on a remote island?

I remember when the US dollar was a valuable currency; markets all over the world wanted dollars, because they were so widely used and exchangeable. So you want your money to be scarce, but you want your currency as widely used as possible.

V. Conclusion

It’s important to treat scarce goods as scarce, abundant goods as abundant, rivalrous goods as rivalrous, and so on. Wall Street treated money, a scarce and rivalrous good, as though it were infinite/non-rivalrous, and look what happened. Power companies, and the politicians they own, treat the environment, which is a rivalrous commons, as though it were non-rivalrous, and we have dying oceans and mass extinctions and other events you don’t want to think about so much that you’ll just get mad at me if I point them out here so I’ll stop. The RIAA and MPAA, and the politicians they own, treat Culture, which is anti-rivalrous, as though it’s rivalrous. They are doing for Culture what Wall Street did for the economy. If you want to help make this better, treat Culture like what it is: an anti-rivalrous good that increases in value the more it is used.

Addendum: Why do I say Culture is not a Commons?

A commons can be a rivalrous or a non/anti-rivalrous good. Being a commons has nothing to do with the good itself, but with the question of how a resource/good is socially treated.

In fact, the mentioned »tragedy of the commons« is a »tragedy of no man’s land«, because a commons always includes agreements about the good can be used. This has been proven by Elinor Ostrom (nobel prize in 2009) in numerous empirical studies.

In case of the sheeps there are shepherds, who can communicate and find an agreement about how to use a pasture in a way, that it is not overused.

Culture can be treated a way, that as many people can use it as possible, e.g. by using a free license and open access. In this case the social agreement has a different shape compared to a rivalrous good, but it is a social agreement! Thus, free/open culture is a commons, too. This a way to defend the anti-rivalrous nature of the good against those, who want to exclude people from using it.

One of commons experts I can recommend is David Bollier who wrote the great book Viral Spiral especially about the digital commons (including culture).

If you are more interested in a taxonomy of goods: I gave a talk on that topic at OKCon in Berlin. However, only the slides are available.

Hi Nina, I must agree with Stefan here. While the nature of a good is important, it still can be treated in socially different ways. And commons can be digital, and therefore anti-rivalrous.

THere are interesting typologies here at http://p2pfoundation.net/Category:Commons

including Stefan’s typology, listed here at

http://p2pfoundation.net/Commons_-_Typology

You – a limited resource, continue to prove, and clarify, your point of view by sharing it so generously. This post is one more example of your unlimited, anti-rivalrous resourcefulness. Thank you.

If you define a commons as “what we share,” then I agree with you. Unfortunately most define commons as shared property, which culture is not. Shared yes, property no.

@Stefan:

No regulations are needed for Culture. The only reason we use Free licenses is because of copyright. Were copyright abolished, licenses would be unnecessary. Anti-rivalrous things don’t need to be “managed,” and their use does not need to be restricted in any way, because they are not diminished by use. But of course as long as copyright restrictions are imposed on us, we have to manage those.

“World-historical defeat of women occurred with the origins of culture and is a prerequisite of culture.” ~Gayle Rubin

Source: Rubin, Gayle. “The Traffic in Women,” Toward an Anthropology of Women (Monthly Review Press: New York, 1979), p. 176.

Michel and Stefan:

I thought about it more and wrote this explanation of why I don’t call Culture a commons. It may help explain why I choose the words I do (when I’m careful enough to actually choose my words, which is seldom). Your mileage may – and probably does – vary.

Addendum: Why do I say Culture is not a Commons?

I’m pretty sure I’ve heard Lessig himself make this observation with respect to the “creative commons” in defining the concept. He obviously chose not to include “rivalry” as an intrinsic aspect of the word “commons”, but the ideas are there.

This would be a great seed for another “Minute Meme” — “Culture is Non-Rivalrous”. Or maybe something catchier, like “Culture is Worth More When It’s Shared!”

@Nina:

Right, that’s why commons is a defense against enclose. However, this is true for rival as well as for non/anti-rival goods. Also abundant rival goods have been enclosed, in order to make them scarce, in order to make them being a commodity. The history of capitalism can be described as a history of enclosure which is an ongoing process — be it rival or non-rival goods/resources, only the measures differ.

On the property argument, I will comment on the Addendum.

The whole identity thing really messes with the IP landscape, because registered trademarks, for example, clearly serve good purpose to protect from rivalrous exploitation. It wouldn’t be good for me to start up a restaurant called “mcdonald’s” and coattail on their well-knownedness or ruin their reputation (if I happen to be a bad restauranteur).

On the other hand, should George Lucas be allowed to extract a fee from Motorola to release a product carrying the name “droid”?

I always thought it was odd when people talked about “preserving” the culture of native peoples, in the sense of locking it away. Preserving a language by attacking people who use it incorrectly. Etc. I’ve always been of the opinion that to keep a culture, you need to popularize it, get more people into it, etc.

Also, I’m surprised that with your License to Love thing, you didn’t mention that love itself is well known to be anti-rivalrous – everyone knows the line from Magic Penny- “Love is something if you give it away- you end up having more!” (annoyingly, that song is still under copyright- OH WELL.)

good article and good points. But are we sure that considering culture as a ‘good’, whose ‘economic value’ increase or decrease, is right? Hasn’t culture intrinsic values, which have not much to do with economic values? Maybe I’m too European to embrace this point. It has to do to what we mean by culture. Of course I agree that facebook and social networks are culture, but when they get quoted on the Stock Exchange and my profile becomes 20 grands in a bank account… Culturally speaking, i wouldn’t say that English language has higher values than other languages. If we had to quote everything in the market, probably yes, but I surely would disagree with such a picture.

anyway, cheers

Intellectual works are rivalrous: http://culturalliberty.org/blog/index.php?id=218

Also see: http://culturalliberty.org/blog/index.php?id=168

I can’t entirely agree with you about culture. Jokes do not get funnier the more times you hear them. Songs lose their power through over-saturation. Designer fashions have less impact once you see cheap ripoffs in every store window.

What all these things share is a novelty factor. Novelty can get used up just like any other rivalrous good — and when it does, cultural products either go into the trashbin (if they were trivial and forgettable to begin with) or they become part of the general cultural endowment.

To me, this suggests that it makes sense to offer a limited term of copyright, tied to the duration of the novelty factor. There are no doubt other possible solutions, but one way or another the presence of rivalrous elements within culture has to be acknowledged.

Songs lose their power through over-saturation.

No, they don’t. That’s a myth invented by people who want monopolies on culture. Also note the distinction between value and power.

Hmm, I sort of believe physical material can be in two places at the same time, I read somewhere it can be possible. xD But as my opinion, we cant be too sure if its possible or not until more info is found. 🙂

But interesting article though.

I like the Identity and Secret part, its pretty much true, a secret is in a room, but once the secret goes out like posted online and one or more people sees, its impossible to walk back into that house. (Unless it was deleted before anyone sees, its more possible to go back in.) It may not be a secret anymore. xD And yeah, Privacy can be important. 😉

My personal observation: The law VS. common sense = law trumps. So many times common sense is obvious, “but the law is” the law. Copy protection being used to bury ideas, is like RC VS. libertarianism. Who owns the writing on this page? Or percentages of the English language I’m communicating with. Don’t comprehend what I’m writing here, cause if someone has already voiced this, I might be accused of plagiarizing. I wish there were something that could be done to straighten this all out. (my punctuation is crap)

A very well put together and written blog, thank you for posting this! Do you have a facebook page or Twitter account? I’d most certainly follow you. 🙂

Nina, you should read (and use) this text :

http://bastiat.org/en/petition.html

😉

Nina, have you considered the possibility that both culture and language can be rivalrous if the people who create and use them don’t want their community to grow any larger, for whatever reason?

Perhaps a good example would be secret prison languages and codes – obviously the people using them would only want a small group of people to be fluent.

Addendum: you make the distinction between private “secrets” and public “culture”. How far are you willing to take that? Is a culture that’s deliberately kept secret by a certain group of people (for example, the crypto-Jews of Portugal) no longer considered a culture because it’s deliberately kept out of public sight? Or perhaps not a very valuable culture? Or perhaps, valuable for the people that have it, which is maybe what really counts? Or maybe diversity is not a good thing, because it can lead to conflict and war?

Go deep enough down this line of thinking, and we get into some very thorny issues…

Nina, you are completely right here. In fact, the psychological term is mere exposure

People forget the history of PAYOLA. Back in the 1950’s record companies illegally bribed radio stations to play their records. They do the same thing now, but found legal loopholes. The fact is, just making people hear it more means it becomes more valuable, more in demand, more culturally relevant.

Sure, there are also people like me who insist: “Naw, I’ve already heard that song. Let’s listen to something else.” but that’s rare.

Hey Nina the link to “culture is not a commons” has an extra double quote in it and is busted…

Um, it works fine when I click it…

Hi Nina,

I love the cartoons on this page.

Are you okay for me to use your two pictures (good commons, tragic commons) in a powerpoint presentation I’m preparing on the tragedy of the commons?

Thanks,

Hans