Venerable author Cory Doctorow and I had this email correspondence this Summer, with the intention of sharing it to illuminate some issues confronting Free Culture and Creative Commons licenses. My thanks to Cory!

May 17, 2010

Hi Cory,

I’m writing to invite you to experiment with what I think is a brilliant innovation from QuestionCopyright.org: the Creator Endorsed Mark.

You clearly laid out your reasons for using -NC licenses in THE COPYRIGHT THING:

“I like the fact that copyright lets me sell rights to my publishers and film studios and so on. It’s nice that they can’t just take my stuff without permission and get rich on it without cutting me in for a piece of the action.” link

The Creator Endorsed Mark effectively achieves the same thing, but without commercial monopolies. As you know, -NC licenses have some drawbacks: there’s no clear delineation between commercial and non-commercial use. You write,

“It’s just stupid to say that an elementary school classroom should have to talk to a lawyer at a giant global publisher before they put on a play based on one of my books.” link

It is stupid, but if the school raises any money to put on that play, or charges for tickets, or any number of other likely scenarios, then it’s commercial use of your work. You know it’s stupid, and I know it’s stupid, and maybe even some teachers and students know it’s stupid, but the school is obliged to obey the law, and the -NC license says they have to negotiate permission. If there’s a legal adviser at that school, they’re not going to allow the play without permission; and if asking for permission is too uncertain or labor-intensive (as it is in almost all cases – a lawyer may not know what an exception yours is), they won’t put on the play.

The Creator Endorsed Mark solves that problem. There is no commercial monopoly to infringe on. Big players – “publishers and film studios and so on” – need your Endorsement. If they cross you and your fans, they have a huge publicity problem; if they obtain your endorsement and cooperation, they sell more copies. The Creator Endorsed Mark increases the monetary value of distributed works, and is an essential investment for a distributor to make. But unlike a commercial monopoly, it doesn’t legally threaten or punish all those other players who are so crucial to a thriving cultural economy: schools putting on plays, other creatives building on the work, and otherwise unimaginable scenarios.

Some of the coolest things that happened to Sita Sings the Blues I couldn’t possibly have imagined, like this sculpture in India, this amazing every-frame-of-the-film poster, and this bicycle wheel video display, all of which are technically “commercial use” and would have been prohibited by an -NC license.

If any players want to go “big time,” the artist’s Endorsement will allow them to effectively compete in the market. Without an Endorsement, they won’t get far. And most of them aren’t planning to get that big anyway; they just want to sell some tickets to the school play, or some bike wheel LEDs.

The Creator Endorsed Mark solves other problems, by addressing the common (and incorrect) assumption that any use of a work implies its author’s endorsement. Widespread use of the mark could prevent such misunderstandings as the Jackson Browne vs. Ohio Republicans case. Browne was unfortunately trying to use copyright to suppress speech. Like it or not, the Republicans paid to license Browne’s “property” fair and square, through his assigned IP managers. Browne didn’t endorse the Republican party or McCain, but how was anyone to know that? Artists shouldn’t have to abuse copyright like Browne did. They can use the Creator Endorsed Mark instead.

Because I have no commercial monopoly on Sita Sings the Blues, all my contracts are Endorsement contracts. I have many contracts with many Endorsed distributors, just as I would had I negotiated “rights.” In fact, when a distributor wants to work with Sita, we just modify their rights agreement to be an Endorsement agreement. I get money, the distributor gets security, and everyone’s happy. As with rights, Endorsements can be exclusive or non-exclusive. Sita’s French distributor has my exclusive Endorsement for all French “territory,” just as they would have exclusive rights to an unfree film. I prefer non-exclusive Endorsements, and have many such deals with US distributors.

The more authors use the Creator Endorsed Mark, the more effective it will become. It will only become standard practice if we practice its standards. Hence this invitation, or plea. Won’t you consider releasing an upcoming project with the Creator Endorsed Mark in lieu of a commercial monopoly?

Thanks,

–Nina

May 17, 2010

Hey, Nina! I’d love to talk with you about this in detail, but

mid-book-tour is too hectic for it! Can we bookmark this conversation

for a later date?

One gloss I’d put on this is that while “commercial” and “noncommercial”

are disputed terrain, a less-disputed (though by no means simple)

distinction is “industrial” and “nonindustrial.” For example, we

regulate (supposedly) the banks and require certain disclosures and

reporting of activities that have parallels in the “nonindustrial”

personal world, such as buying a lunch for a friend, loaning your son

money, or transferring money to your wife’s account. There is a scale at

which that activity ceases to be “personal” and becomes “industrial” and

there are zones on that curve in which reasonable people might disagree

about whether we’re talking about a bank, an investor, or just a friend.

Nevertheless, regulating banks is something I support.

Likewise, I support regulating the entertainment industry’s supply

chain. Copyright as presently or traditionally construed might be a

suboptimal rule-set for that industry (I think it’s historically tilted

to the favor of capital against the interests of labor), but that’s not

to say that there shouldn’t or can’t be a set of rules that govern that

industry to ensure fair dealing and to redress inherent power and

negotiation differences.

But let’s pick this up later — I’d love to dig into it with you when

I’m not doing 4 school stops, 5 interviews and a bookstore appearance

every day!

Cory

LATER….

June 27, 2010

Hi Cory,

The distinctions between “commercial” and “non-commercial,” “industrial” and “non-industrial,” miss the point I think. The meaningful distinction is between MONOPOLISTIC and NON-MONOPOLISTIC (Open, Free, Libre, etc.). Monopolies on information damage culture, artists, audiences, and ultimately commerce as well.

When we met at your book signing last month, I recall you said that publications could enclose free works, even share-alike works, by republishing them alongside additional material under more restrictive licenses. If enforced, Share Alike licenses could restrict such enclosures, but that could cut off the authors from those publishing opportunities. You seemed to favor -NC licenses because they preserve opportunities for authors to be published within enclosed systems.

But how does maintaining commercial monopolies over works do anything to improve or solve the problem of monopolies on information? The scenario you describe assumes publishers will keep enclosing no matter what, so if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em. But the more works are Share-Alike/CopyLEFT (real copyleft, without commercial monopolies), the weaker enclosure systems become. If the problem is enclosure of works, -NC licenses are perpetuating it, not solving it. If we don’t copyLeft our works, publishers sure as hell won’t.

If getting money for the artist is the primary concern, the Creator Endorsed Mark should offer reassurance, as should my own experience. You said that my experience with Sita offers “only one data point,” but I think the entire Free Software Movement offers plenty more. As do true copyLeft books, like Karl Fogel’s. Karl’s copyLeft license sells more paper books, without the -NC restriction. (Also without even the CE Mark, which didn’t yet exist when his books were published; the kind of commercial competition so many authors fear is quite impractical in real life.)

I agree that industry needs some regulation. Primarily, government should step in to BREAK UP MONOPOLIES. Creating more state-backed monopolies is an inversion of how government should regulate industry. As long as we support commercial monopolies, expecting proper government regulation of industry will remain ridiculous, if not outright hypocritical.

I pointed out an SA license can prevent abusive exploitation as well as an -NC license. But importantly, it encourages all other exploitation; it is pro-commerce. -NC licenses come at a cultural cost. You said there’s very little enforcement of -NC works against many (minor?) commercial uses. But you can’t count the ways -NC works are NOT used, or considered for use, in worthy projects. I myself won’t work with -NC material, not only because of the unknown hassle of obtaining permission and the cost of licensing fees, but also because I won’t release my own work under a commercial (or any) monopoly. -NC licensed work is incompatible with genuinely Free work. It is, however, very compatible with an abusive monopolistic system which needs to change, one that authors are in a unique position to help change.

–Nina

June 27, 2010

Here’s my perspective: the purpose of any cultural policy or regulation

should be to encourage a diversity of both participation and works (that

is: more people making art, and more kinds of art being made).

ISTM that your assertion amounts to: “Whatever forms of participation

that come into existence as a result of the capitalization opportunities

that accrue in an exclusive rights regime, they are dwarfed by the works

that lurk in potentia should such a regime perish.”

IOW: we unequivocally get *some* participation in culture as a result of

exclusive rights regimes, some of which would not exist except for

exclusive rights. You believe that if this regime and the works that

depend on it was to vanish, the new works that would come into existence

as a result would offset the losses.

I don’t know how either assertion could be tested. We both have

firsthand experience of both modes of creativity — I know of works that

wouldn’t have been capitalized absent the higher returns expected in the

presence of exclusive rights; I also know of works that could only have

been made in their absence.

But I don’t accept the argument that simply because monopolies are

always bad, their absence is always preferable. It’s clear to me that in

rival goods – say, my underwear — my monopoly is preferable to its

absence. I’m willing to stipulate, at least for the sake of

investigation, that some exclusive rights regimes in non-rival realms

produce better outcomes than their absence would produce.

I view exclusive rights as a purely utilitarian, instrumental question,

and one that’s admittedly hard to get right — the exclusive right

needed to get a complicated project made today is unlikely to be handed

back gracefully tomorrow when it is no longer needed because technology

has simplified the project.

But lots of policy questions are hard to get right; that shouldn’t

disqualify them from consideration for regulation (other rules that are

hard to get right include finance, building codes, zoning laws, child

protection, etc — I’m OK with the state having a go at them, though,

because I’ve seen that in the absence of rules, many of the outcomes are

very bad indeed).

Some economists have tried to answer the question as to what kind of

exclusive rights produce the best outcomes for which media. I confess I

don’t have the math to follow them (Rufus Pollock is one; I can’t give

an URL as I’m on a train with no network access ATM, but it’s

googlable). But I’m amenable to the idea that we can empirically answer

the questions:

At this moment in time:

* Which media

* Need which exclusive rights

* To produce the best outcomes?

Take Sita — could we have avoided the whole Sita problem, if, for

example, sync rights were nonexclusive? What if they were statutory, and

a fixed, minimal percentage of net income (an “economic right” instead

of a “moral right” in WIPO talk)?

One result of an instrumental view of exclusive rights is that they

should NEVER be retrospective — no one ever went back in time and

recorded an extra record because we gave her an extra 20 years copyright

on the works she was making back then. So at least in this regime, you’d

never have the Sita problem (I know that your concern is larger than

this, of course).

I confess that I don’t have any empirical reason to believe that “no

rights” produce worse outcomes than “some rights.” But intuitively, it

makes sense to me.

I think it makes sense to you too — you believe that limited exclusive

rights for the purpose of preventing fraud (trademark protection for the

CE mark) produces a better outcome than its absence. At least some

artists I know — Negativland, the Yes Men — rely on being able to

commit “fraud” as part of their art (and I like their art) and chafe at

this regime. Arguably, an enormous quantity of potential art dies in

utero because its creators are too afraid of a trademark lawsuit to go

ahead with it (trademark, as you know, doesn’t expire, enjoys no fair

use exemptions, and represents a major moral hazard in that it requires

that its users actively harass people who use the mark in a generic

fashion, even where the use isn’t a violation of trademark law!).

I’m sure we could construct a

consumer-protection/fair-competition/anti-fraud trademark-style regime

that allowed the Yes Men to pretend to represent Shell Oil without

allowing Shell Oil to pretend to be Nina Paley, but if you’re willing to

stipulate that *this* regulation can be fine-tuned to produce an outcome

you’re happy with, why not other kinds of exclusive rights?

Cory

June28

Dear Cory,

I am quite dubious about exclusive rights = higher returns. Higher returns come from First Mover Advantage, making products available and affordable, and publicity, all of which can be achieved (often better achieved) without artificial monoplies. Sellers who meet their customers’ needs have nothing to fear from “pirates”; there is no incentive to compete against a product that is already available and of high quality. Furthermore, Creator Endorsement adds value to goods that are otherwise equal.

I don’t accept the argument that simply because monopolies are

always bad, their absence is always preferable. It’s clear to me that in

rival goods – say, my underwear — my monopoly is preferable to its

absence.

Ownership of scarce good != monopoly. You know this. I own my copies of Sita Sings the Blues. You own your copies of same. Neither of us have a monopoly on copies of Sita. To call ownership of tangible property “monopoly” is disingenuous. I am not against ownership of tangible property.

I view exclusive rights as a purely utilitarian, instrumental question,

I view them as a Civil Rights question.

and one that’s admittedly hard to get right —

Because they always violate Civil Rights

the exclusive right

needed to get a complicated project made today is unlikely to be handed

back gracefully tomorrow when it is no longer needed because technology

has simplified the project.

Indeed, Civil Rights are never “handed back gracefully,” as history shows us.

Some economists have tried to answer the question as to what kind of

exclusive rights produce the best outcomes for which media.

And some have answered in a sensible way: NONE.

What if they were statutory, and

a fixed, minimal percentage of net income (an “economic right” instead

of a “moral right” in WIPO talk)?

Culture is not a commodity. Furthermore, there are no “rights” in non-rivalrous goods. And now that I know what Freedom is, I’m not going back to the false ownership regime I accepted before.

I confess that I don’t have any empirical reason to believe that “no

rights” produce worse outcomes than “some rights.”

The “rights” you refer to are really restrictions, or “zero-sum rights”: they are always exactly balanced by the taking away of someone else’s rights. The more rights someone has to restrict their work, the fewer rights others have in their copies of that work.

The rights I am talking about are positive-sum rights. This is an important distinction that you gloss over when you compare “no rights” to “some rights” in your sentences above. I am also talking about rights – Civil Rights – the difference being that my rights are not also restrictions in exact proportion to their strength as rights.

But intuitively, it

makes sense to me.

Human brains are wired for a world of scarcity. In the digital age, copies of cultural works are abundant. Reality is changing faster than most peoples’ “intuition” can keep up. Abundance of food has exceeded human “intuition” about food scarcity, hence widespread obesity. Now is a good time to pay attention to the reality of abundance, not just what “intuitively makes sense.” My own intuition finally aligned with the reality of cultural abundance, but it took a lot of “suffering unto truth” for that to happen.

you believe that limited exclusive

rights for the purpose of preventing fraud (trademark protection for the

CE mark) produces a better outcome than its absence.

An identity is a scarce/rivalrous good. An identity is diluted by fraud, and in fact asymptotically approaches zero value to all parties (and thus to society) as fraud increases; whereas a copyrighted work’s value to society is not diluted by replication.

Trademark is lumped together by lawyers with patents and copyrights as “Intellectual Property,” but they are different. Of the three, only Trademark has any justification for its existence. Our Trademark system is corrupt and in need of reform, but it is not fundamentally bankrupt like Copyright, because Trademark addresses scarce goods, not infinite ones.

I’m sure we could construct a

consumer-protection/fair-competition/anti-fraud trademark-style regime

that allowed the Yes Men to pretend to represent Shell Oil without

allowing Shell Oil to pretend to be Nina Paley, but if you’re willing to

stipulate that *this* regulation can be fine-tuned to produce an outcome

you’re happy with, why not other kinds of exclusive rights?

1. Because Trademark is about scarce goods (identity) and Copyrights are about non-scarce goods.

2. Because I, like everyone, am opposed to fraud.

I support laws against fraud. I’m not confident Trademark is the best system. But whatever the shortcomings of Trademark, at least it is related to scarcity.

Best,

–Nina

June 28

Sure, some harm *may* occur when someone fakes your mark. But what about

situations in which none occurs (my toddler pastes a CE mark on a

picture she’s drawn of Sita and sticks it on the wall at day-care)? Or

what about situations in which harm occurs to the markholder but benefit

arises for a third party (The Yes Men pretend to be Shell Oil, make

Shell look stupid, but make good art and good commentary)?

An existing copyrighted work’s value isn’t reduced by duplication, but

we’re not talking about existing works, we’re talking about *potential*

works. Your issue with NC licenses is that some artists may not make a

work because of the noncommercial restriction; I worry that some

capital-intensive art won’t exist without the restriction.

….

All exclusive rights arise from a social contract. It’s clearly

*possible* to create a social contract that awards exclusive rights to

nonrival goods. I think you mean “Not awarding ‘rights’ to nonrival

goods produces better outcomes than awarding rights.”

The rights to nonrival goods are imaginary, but so are all other rights.

A Martian looking through a telescope at my underwear, your house, and a

patent filing for a Franklin Stove wouldn’t necessarily see any reason

why some of these should or shouldn’t be exclusively reserved for some

peoples’ use.

The reason I use words like “holder” and “rights” as opposed to

“property” and “owner” is because I reject the idea that copyright is

property, or that property metaphors are a good way to organize cultural

policy:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2008/feb/21/intellectual.property

….

(The CE mark could work for) some audiences and some works.

I’m all for breaking the discussion

over culture into two pieces: the social transaction and the economic

one, but you’re mixing them here.

People pay higher prices for goods with a CE mark because of a social

transaction. They feel good about it because they’re considering a

holistic picture of the works they enjoy and concluding that they want

to support an artist in the hopes that she’ll make more works they

enjoy. This is a social transaction.

People disregard CE marks because they aren’t counterparties to the

social contract it represents. For example, I don’t pay for mindless

blockbuster shoot-em-up pay-per-views in hotel rooms (one of my vices)

because I have any social investment in the creators of that work (I pay

because it’s easier than not doing so). This is an economic transaction.

Some kinds of works are more apt to create social contracts than others.

Some people are more amenable to countersigning social contracts than

others. Some artists are better at inspiring social contracts than

others. Even without a CE mark, all these are fitness factors for

commercial AND artistic success; the CE mark industrializes the process,

but it’s just icing on the cake.….

….I believe in civil rights, but I think that civil rights don’t

exist without policy underpinnings. The right to water, for example,

depends on policies related to fair aquifer management and many other

issues. Fair aquifer management involves some empirical questions and

some ideological questions, and the way you figure out whether you’ve

got the right policy is whether access to water is increasing or

decreasing across the largest number of people in the largest number of

contexts.

Likewise, access to culture is a right, but it can’t exist without

underlying policies.*

(*How I failed to respond here, but should have: water is rivalrous, culture is non-rivalrous. Comparing culture to aquifiers is the whole problem. If you divert the river, my village doesn’t have water any more; if you copy my song, we both have it. This is a perfect example of why property rules can and should apply to rivalrous goods. Culture is not a rivalrous good. –NP)

June 28

Hi Cory,

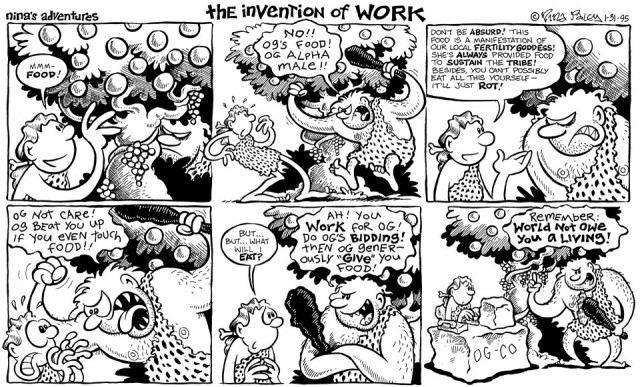

I’m interrupting this argument to share an old comic about property:

More points coming soon.

–Nina

June 28

Har! LOVE IT!

Cory

June 28

Hi Cory,

I’m glad to read that your referring to your “rights as the copyright holder” is about something else. Since this started as my plea for you to try using the Creator Endorsed Mark instead of a commercial monopoly, maybe that outcome is still possible.

How can a monopoly inflate prices without

increasing returns?

By reducing or eliminating purchases. Look at the Big Media industry. The big media conglomerates have a monopoly on licensing rights to old music. They demand inflated fees to use it. They make no money from all the films that had to remove those songs, because their producers couldn’t pay the fees. They make no money from the films that can’t be released at all, nor the ones that never get made in the first place. The inflated prices don’t increase returns for industry, but they do grind progress to a halt, and stifle speech.

Projects with -NC licenses can easily make less money for similar reasons. If an author assigns their monopoly to a distributor who does a poor job, their work is seen less. Without commercial competition, many films are killed by their own distributors. Commercial monopolies are bad for commercial artists.

Some kinds of works are more apt to create social contracts than others.

The CE Mark is truth in labeling, which is detrimentally absent in current commerce. It also separates Endorsement from use, preventing tragedies like this latest from David Byrne.

What’s more, physical property ALSO requires policy to exist.

The best justification for property is that it is a mechanism to minimize disputes. Private (as opposed to personal) property rights are social rules to discourage fighting over scarce resources. I’m not saying this justification is accurate; from the cartoon I sent earlier, you know I also believe private property comes from “original violence.”

I don’t want to argue over physical property here. Whatever the problems of physical property, they are multiplied a hundredfold in imaginary property like copyright. Property policies should minimize disputes over scarce resources; IP creates disputes over infinite resources.

I think you mean “Not awarding ‘rights’ to nonrival

goods produces better outcomes than awarding rights.”

OK. Sort of like, “not shooting your neighbor produces better outcomes than shooting them.” Works for me.

We pretty much agree on Trademark, actually. I do think we need better anti-fraud mechanisms than Trademark. That’s all we’ve got in the current regime, so that’s what QCO is using for the CE Mark. If you have better ideas, please share.

And now please tell me why you choose commercial monopolies over Freedom and the CE Mark.

Best,

–Nina

June 28

Copyright is purely a restriction on access to culture.

Well, rules about aquifers are restrictions on access to water, but

they’re also part of a sane strategy for water management.

But I don’t think copyright is “purely” a restriction. A “pure”

restriction would be one that exists absent any other goal — where the

restriction was the end, not the means. You might disagree about what

incentive it presents, but the formal basis for it is to provide an

incentive and we both know people who find that incentive compelling.

My argument is that some capital-intensive works that we can point to as

being good art and of having spurred a lot of cultural activity exist

because investors were confident in a period of exclusivity.

Certainly I know that Tor Books

puts less money into marketing and promo for PD titles it reprints than

it does for original works (and marketing and promo are two of the

seriously capital intensive parts of selling books). I don’t know of a

single publisher in the world who capitalizes the promotion of PD

reprints as much as in-copyright editions. I think that’s a pretty good

prima facie evidence that, industry wide, exclusive rights produce

contributions to creative endeavor that wouldn’t exist in their absence

(there’s nothing in the world that stops, say, Dover, from touring

scholars with new editions of PD titles, from buying end-caps and co-op

in major retailers, and from buying ads and paying for freebies and

events at ALA and BEA, but they never, ever have).

I couldn’t afford to personally capitalize the

publicity and marketing that Tor can front me, and that makes an

enormous difference in both the reach and the net income. No

self-promoted novel has ever been a NYT bestseller (or even an

Indiebound bestseller), and the income from those commercial attainments

has freed me to write more ambitious books than I could have written

while working my dayjob at EFF (which I was only able to quit when my

Tor royalties reached a certain threshold). For example, for my last

book, FOR THE WIN, I fronted about $20,000 in research expenses (travel,

transcription, etc), and took about seven months off to write it. I

certainly couldn’t have done that while working at EFF (I got three

weeks vacation/year there).

….

I agree that giving the recording industry really huge catalogs that go back

forever in order to allow them to milk the infinitesimal fraction that

they actually care about has been an artistic and policy disaster. But I

think that for the winners in the stilted, shitty market that this has

created, the profits have been enormous (partly because they get to shut

out all competition and monopolize distribution channels and so command

even more lopsided deals from creators).

June 30

Hi Cory,

Interesting. I now think of one work that doesn’t exist (yet) but would if a conventional copyright monopoly were available for it: A Sita Sings the Blues graphic novel. (I have no desire to produce such a work myself – if I did, it would exist, believe me.) 2 established publishers wanted to produce such a book, and were willing to hire writers to produce the adaptation, and designers to adapt the artwork, but only if I were willing to undermine the -SA license and grant them a monopoly over the result. I wasn’t willing, and the book(s) weren’t produced.

This is a business model issue. The publisher(s) could have made as much if not more money publishing a freely licensed book. It’s not the monopoly that’s the incentive, it’s “doing business the way we’ve always done it and the only way we can imagine doing it” that’s the incentive. That is very different from the monopoly itself being the incentive.

Money is a great incentive for publishers. Monopolies are not necessary to maximize money – you’ve already agreed that’s true in some cases. I want my publishers and distributors to maximize their revenue too, and I know this can happen without monopolies – again in some cases, like my case, and probably yours too. But the publishers don’t know that (and I can’t tell whether you do). I’m in an unfortunate position with book publishers: the ones that publish Free-licensed books are mostly in tech (O’Reilly), and the ones that do popular culture and art books are years away from even considering Free licenses.

So “adhering to a business model we’re used to” is being confused with monopoly itself, as an incentive for financing, creating and publishing certain works. The Creator Endorsed Mark is a great alternative to commercial monopolies, benefitting publishers, writers, and the public. But it’s new and different, and right now that is its greatest obstacle. You might consider that your books would benefit your Endorsed publishers just well with a CE Mark and a Free license, as with a commercial monopoly. But would your publishers consider that? And is it worth the trouble to you to try to persuade them?

I’m not going to argue here that Freedom + the CE mark would equal or increase revenues for all works. You’ve already acknowledged it would for some. I’m confident yours are the kind it would work for very well. So now I’d like to know whether 1) you agree with my estimation that your work could do just as well with a free license and CE mark as it does with a commercial monopoly, and 2) whether it’s worth your trouble to actually try it, which would involve persuading your publisher, which is a lot of work and may not succeed.

Best,

–Nina

July 1

Hey, Nina! Well, like I said in the last volley: I don’t believe that my

books would reach the same scale of audience nor have the same impact

w/o Tor and it’s substantial marketing investment.

July 1

Right! I’m not suggesting you self-publish. I’m suggesting you ask Tor if they’d publish a book under a Free license and with your Creator Endorsement, giving them the exclusive (or however you negotiate it in your contract with them) privilege to display the Creator Endorsed Mark. The CE Mark is for publishers and distributors.

–Nina

July 1

Actually, I *did* suggest something similar for the book I’m working on

ATM, Pirate Cinema, and both my agent and my editor told me I was nuts.

With neither of them behind it, there’s no chance I’d be able to sell it

to them…

Cory

July1

AHA!

So why did we bother with the whole argument? 😉

The problem is not that commercial monopolies are beneficial, necessary or even useful. The problem is that publishers, editors, agents, distributors – “the industry” – are not willing to consider alternatives to business-as-usual. Except maybe O’Reilly. I like publishers, and recognize their value to authors, and wish more of them were as forward-thinking as O’Reilly. But just because they aren’t, doesn’t mean their reasoning is sound. We don’t have to defend monopolies just because the publishers we love still cling to them.

I like my own distributors much more because they don’t have a monopoly on my work. You are rather exceptional in that you have an excellent relationship with a publisher who is taking care of you. That may be more common in books than films, but it’s rare in any field.

When you suggested “something similar” to your agent and editor, did it include the Creator Endorsed Mark? Look how shiny and pretty it is:

If you want to try pushing your agent and editor again, we’ll support you. Please don’t give up!

Best,

–Nina

July 1

Hey, Nina! Well, I didn’t talk abotu CE, but we did talk about the idea

of there being an official version and unofficial onces — even the

notion of just allowing commercial *translation* or *adaptation* and it

wasn’t a go.

July1

Well, CE has the advantage of being simple, clear, already in use (I have the contracts to prove it!), and having an authoritative–looking mark.

You could point these things out to your editor/agent/publisher. I’m not saying you’d convince them, I’m saying it’s worth pushing the idea. That’s valuable in itself, regardless of the consequences. That’s why I’m arguing with you – not to convince you (although that would be nice), but to honor the principles I believe in by giving them a voice, which incrementally helps move them closer to reality.

–Nina

Interesting how Cory sometimes reverts to examples of scarce goods when trying to bolster his arguments; bits are not scarce, and they only become artificially so when DRM is used. Isn’t he anti-DRM?

http://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2009/04/doctorows-law

Why does Cory want to put a lock on culture?? 🙂

Very good question. I too am puzzled that he doesn’t see that copyright is simply social DRM. To paraphrase Cory: “No one woke up this morning and thought, ‘gee, I wish there was a way I could do less with my music, maybe someone’s offering that product today.'” Oh, wait, I didn’t even have to paraphrase: that’s the exact quote. You can’t even tell whether it’s talking about copyright (social restrictions) or DRM (technical restrictions).

The thing I notice most is that a civil rights argument is countered with a business model argument (though to be fair, the latter on the grounds that that it in theory would cause more or better culture to be produced, though I don’t think there’s any evidence for that overall). It might well be that Tor wouldn’t be able to front him as much for a single novel if they used a non-restrictive business model, I don’t know. But the tradeoff where we get that in return for not being able to share freely with each other really stretches the boundaries of the word “policy”. Sure, copyright is a “policy”; every law is implicitly a policy. But downshifting to a neutral-sounding word like “policy” doesn’t change what’s actually going on.

“If getting money for the artist is the primary concern, the Creator Endorsed Mark should offer reassurance, as should my own experience. You said that my experience with Sita offers “only one data point,—

Funny that Cory said that. Couldn’t the same thing be said of his Creative Commons ebook experiment?

Cory asked me to reinsert some edited bits, which I just did (he approved the first edit on the run, and had second thoughts upon a second reading). So have another look to see if his arguments now address the scarce/non-scarce issues. I think his argument is: “property restrictions are made-up concepts we apply to rivalrous goods for socially beneficial reasons, so why not apply similar concepts to non-rivalrous goods too?”

To which I would respond, “property restrictions are bad enough on rivalrous goods, why apply them to non-rivalrous goods too?”

But I don’t want to put words in Cory’s mouth. Lots more words are above now, for those willing to read them all.

I appreciate the obvious hard work you’ve both put into this correspondence. I must admit that I know very little or nothing about copyright, artist’s rights and such…but I do know when a topic is being handled above the heads of your average culture consumer.

Honestly, just as I’m scared of basic government agencies impinging on my creative rights, I would be as scared (or more scared) of you two being in any sort of control of my (or others) creative output.

In other words, beyond a certain point what you’ve been discussing becomes more of the “same old”

Artistry and creative endeavors should at all times be treated as what they are…simple activites that often bring happiness and (if you have a good agent) maybe a little money.

I have no idea what either one of you is typing about.

Best wishes, though! And hopey ou’re able to figure it all out on your own verbose terms.

Thanks much for posting this.

I think the CE mark is probably worth an experiment… My problem with it is that I don’t think its absence would be as devastating as Nina suggests. Particularly in situations where the fan base isn’t huge, or if the fan base isn’t attached to the author. Every Alan Moore movie to date would, if he could have done it, have been released with a big “Creator Did Not Approve” stamp on it; but did his obvious distaste for the adaptations prevent them from getting made, seen, and (for the most part) earning a profit?

I simply don’t think that most of the public is engaged enough to care–or that maybe everybody has a few things they’d care about, but everybody’s pet creators are different. An author with a cult of personality attached to their work–JK Rowling, perhaps, or Stephanie Meyer–might be able to doom an unauthorized printing or adaptation, but most authors simply don’t have that kind of power over the public at large. If a major movie studio decides it wants to spend 100 million dollars making and promoting an adaptation that the original creator did not endorse, they’re not going to be significantly worse off for the lack of it. True, they might deal with the author, just to dot and cross their is and ts, but if the author refused, they’d probably just do it anyway.

The endorsement idea isn’t new–Tolkien did the same thing, writing a forward in the edition of Lord of the Rings stating that this was the only approved edition and all others were pirated copies, and I’m sure the practice goes back to Gutenberg in one form or another. But it’s still not going to work, because creators can’t count on public opinion to protect their work. Public opinion is fickle, and can be easily swayed by large marketing budgets. You need the law on your side if you’re going to protect your work.

Cory also seems to be ignoring recent discoveries indicating that large monetary incentives actually tend to bar people from high-functioning, creative work. A more merit-based art community might actually produce wonders if we shucked our capitalist illusions.

He makes some interesting arguments, but, despite personally being on the fence, I can’t help but feel like it’s a classic case of Haves forgetting what it’s like to be a Not-Have.

Kyu – it’s the combination of the CE Mark with the CopyLeft/Share Alike license that works.

Nina,

I highly respect Cory, but I think that here he’s wrong and you are right. CE+copyleft sounds really great.

Take care,

Dav

Nina, Cory,

This is very very educational. One thing that causes me concern is the statement:

“I confess that I don’t have any empirical reason to believe that “no

rights†produce worse outcomes than “some rights.†But intuitively, it

makes sense to me.”

I don’t understand why “no-rights” might produce worse outcomes. As far as I know many artists and many programmers create because they must. Many farmers grow because they must (not because of financial incentive). Many inventors invent because they must (not because they have a commercial motive).

Obviously there are plenty of artists, coders, inventors, farmers who do their work with a financial motive, but this does not make their work any more (or less) valuable (i.e., better/worse) than those who create because the act of creation is satisfying.

This seems to be the premise of much of the copyright/property debate. That innovation comes only when creativity is “protected” seems like a bogus argument given that I’ve experienced comics, folk musicians and folk artists who get nothing but community respect for their works (i.e., they have no formal “rights”).

@Nina (but anyone really)

In most fields biology is a source of inspiration or even “knowledge”, as it has been around long enough to come up against nearly every problem. Birds (or perhaps the proto-bird) invented the aerofoil we see on planes, geckos apparently can leverage quantum mechanics to stick to anything. (An interesting aside; I wonder if any patent has been successfully reversed due to a pre-existing “device” already naturally selected and therefore in the public domain.)

Copying and modification is fundamental and “progress” halts when these are restricted. Quite what parallels exist, I haven’t fully thought out, I am no biologist, but DNA/RNA seems as close to IP than anything in nature. (I think the distinction between property and IP is utterly arbitrary, everything is just property or even just information. By extension, the same can be said of patents and CR; these are the same thing. Patents govern tangible arrangements of atoms, but on some level, however low, IP must manifest in the physical.) There are obvious rules governing access, what can be combined with what chemically, sexual behaviour and anatomy (the rather grotesque DRM measures and counter measures seen in bed bugs and ducks reproductive systems come to mind), and there are even pirates: viruses. Research is embryonic, but there are hints at horizontal evolution where the viruses may disrupt the DNA information with positive affect.

I think the point I am ambling towards is, could there actually be real objective natural laws governing copying and modification that can be extracted from science, rather than subjective self serving laws which are created by the incumbent to maximise longevity and prosperity?

From a socio-ecomomic-political view point, perhaps it is the biases of the monetary system that forces legislation to favour restrictive measures. I like what Douglas Rushkoff has to say on this. It too has a copyright monopoly where only the Bank of England (and the

other centralised equivalents (US: Fed Reserve?)) has the “right” to print money, and to have the only legal tender. (The alternative to this is local currencies that can run simultaneously and the value is one of abundance; hoarding is not beneficial.)

This influence leads to an inevitable warping of the legal framework, and a leaching of all information to the elite, patents are bought, IP is bought, and the elites get stronger. And repeat. Therefore the solution is not then to champion the anti-copyright movement, but to dismantle the system in which exclusivity and scarcity is the source of power; forego capitalism in its current form?

I like the fact that you’re trying to “fix” the IP rights given to creators rather than abolish them altogether. But different creators want different rights.

Kyu makes a good point that some adaptations of a work (particularly film adaptations) are not going to give a good goddamn about the CE mark. There are movies seen by 10 million people that are based on a book 100,000 people read. The other 9.9 million were sold on the trailer and film marketing and wouldn’t care if a CE mark shows up or not. Of the 100,000 who may be fans of the author, how many would be so dedicated as to skip the film?

And even so, you have to create a HUGE education campaign to ensure people know what the CE mark is and give a damn about it. The cost of such an education campaign would be massive. I can go into a room full of *tech workers* and ask them what CC-SA means and they’ll give me a blank stare. Copyright and the copyright symbol are cultural touchstones because they’ve been around for centuries.

But original copyrights were for 7-14 years, then 28, now life plus 75 and possibly longer once Mickey Mouse’s copyright is about to expire again.

In this world where works live on for so long, we might create a tiered level of exclusivity… 7 years for all uses, followed by 30 years of copyleft (you can use it freely if you adhere to the copyleft license, but you have to buy a license if you plan to copyright the resulting work), followed by public domain but you or your heirs can still sell/license the CE mark which may have some value.

Has Cory ever weighed in on copyright *lengths?* Because that seems to me to be the most onerous part of the current system.

I’m pretty sure Cory thinks copyright terms are too long. As do I, of course.

Nina, your writing is absolutely fantastic! I am a musician using SA licenses with my work and after having read this discussion, feel better equipped to explain my motivations, and my belief that I benefit from releasing my work under copyleft licenses versus non-comercial licenses. Thank you for the heads up on the CE concept as well!

That Creator Endorsed Mark emblem makes me want to vomit.

Out with the old and in with the old.

Nice cartoon, but I’m wondering if the big “alpha male” and the little guy prehistoric men wouldn’t have been fighting over an animal (or several animals) – it’s fairly well accepted that prehistoric man lived off of meat and not from fruit and vegetables (primarily) – otherwise a cute cartoon

Thanks so much for publishing this.

I’m not actually persuaded by either of you, but that’s not uncommon. I don’t see how there can be a one-size-fits-all fix for the shambling mess of copyright. Setting aside the political realities of replacing the current regime with something better, there exists the problem how things get produced in the real world. The rules that enable the creation of Waterworld-style movies obviously suppress the creation of other works, but it is also true that some sets of rules that enable creation of those suppressed works would make it unlikely that Waterworld would get made (in that particular case, perhaps that’s a feature.) So there’s always a tradeoff, and tradeoffs become questions of value judgements and personal approaches.

The personal approach issue seems to be shining through here – Cory can’t see how he can continue creating the way he is now under the scheme you propose. This also happens with the occasional aging rock star that pipes up and says that The Pirate Bay would have killed their career if it existed back-when. And the thing is, they’re both correct. Now, I think Cory could, if pressed, find a new arrangement that would work for him in your scheme, but inertia, lack of incentive and uncertainty estop him seeking one out, which is simply rational behavior. This is also why $aging_rockstar is correct – they would have had a very different career, or perhaps none at all, under different economic and imaginary property schemes. (I’ll leave aside that crusty old rockstars who live on royalties are doing the youngin’s like Amanda Palmer no favors, which is a distinction that matters in the overall debate, but doesn’t in terms of trying to figure out what the best imaginary property regime is.)

So, in a sense, I think I tend to come down a bit closer to Cory’s take – treating imaginary property as a strictly instrumental policy tool makes sense, in that what at least *I* want to see is an environment in which everyone who wants to make something has at least a chance of doing it, and if that way is using CE, great! if that way is using an -NC license, also great! And this does mean that I come down on the side of doing whatever we can to roll back infinite -1 copyright terms, blowing up most of the patent system, and (where I may well lose you, Nina) substantially rejiggering trademark law. Such a retooling may well mean that the world will be deprived of Waterworld II: The Rest Of The First, I do think the tradeoff is worth it. But it is important to be conscious that we are making tradeoffs that are laden with a value judgement, and that these choices can and will have real impact on the artistic output and careers of real people.

To switch gears a bit, the idea of copying as a civil right on a moral plane makes perfect sense to me. As I just asserted that I think viewing imaginary property rules as a strictly instrumental tool, this is uncomfortable, and after reading your take on this, I have some more thinking to do on what I thought was a settle question for me. (So thank you for that!) While the idea of a moral right to a copy of Waterworld strikes most people as a bit silly, when the idea is reframed to thinking about McGraw-Hill profit-maximizing on the backs of broke students’ access to understanding physics, folks are more likely to consider the possibility of alternate schemes. (especially if they happen to have kids in college).

I did want to note that you seemed to avoid the question of what to do about the Yes Men. It may well be that they would be one of the casualties in your scheme, and perhaps that is “worth it”. But I think it does need to be addressed.

I also have some more thinking to do on your conception of ownership of identity. This crosses a lot of lines that have little to do with copyright (to be partially U.S.-centric, it implicates libel law, the idea and propriety of gossip, the 4th amendment, issues of compelled speech, and ideas about the function and manifestation of memory, just for starters). I think, and the question of the nature of identity in our culture is going to become a fiercely contested issue in the near future. But as mentioned, this only partially intersects the scheme you’re talking about.

All in all, a great bundle of things to think about! Thanks a bunch for publishing this, again.

Thanks. I’m not attached to trademark; it’s part of the existing legal regime we can use, but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be replaced with something better. I support any and all IP reform, but meaningful IP reform is unlikely to happen in my lifetime. It’s what we can do right now, in this world, with the tools at hand, that interests me more.

Oh, and what I’d do about the Yes Men? Nothing. I’m only interested in addressing fraud, not satire. Same with kids scrawling trademarks for fun: that’s not fraud.

I agree that what we can do now is the more interesting question; sorry if I ended up spending too much time on theory. I do think that being able to place incremental steps in the right direction into an overall vision of what is “correct” is useful, not to mention strategically smart for when aging rock start bellyaching and movie execs start babbling about popcorn farmers.

I guess my comment about trademark was partially that were I dictator, it would be useful only as a certification of origin – $big_corp actually made that can of soda, Nina Paley actually made that movie. If people can build reputation or branding on that, great, but facilitating the branding aspect shouldn’t be the legal function of the mark.

More generally, I don’t see how CE fixes issues like Byrne’s. That is, I don’t think he’s be any happier with opportunistic politicians using his music if he were in a world with a well known CE endorsement scheme that the pol had to omit. It seems to me that the signaling problem Byrne was upset about is not just the implied endorsement from Byrne the person, but rather also the perceived cheapening and redefinition of the song itself. By analogy, I think he saw it as sort of like taking a quote out of context to reverse the meaning the speaker originally was conveying. A CE badge on the ad could remove the ambiguity as to whether or not the original artist endorsed the pol, but the absence of a badge doesn’t really do much to stop people from associating Born In The USA with jingoist nationalism. Byrne really did want the power to stop someone else from “remixing” his song, and absent that, a big stick with which to dissuade others from doing it in the future.

My mind always reverts to the reality that copyright (all copyright) is built for the rich amongst us.

You must both admit the basic expense of acquiring any sort of copyright for anything is notmally beyond the grasp of your average musician, inventor or fine visual artist. Vague copyright concepts such as “Creative Commons” (what exactly is it?!) and now “Creator Endorsed Mark” (ooh, goody! how hip!)

only leave me with many bad tastes in my mouth.

Instead of wasting time blabbering about copyright and vague replacements for copyright, how about addressing future poverty in America, a current collapsing economy, liars in office (of both parties), etc

Believe me, there won’t be much need for copyright or copyright lawyers, iPods or well-designed stationery if no one has the money to finance such neato things

This may be a stupid question, but would it be possible and/or desirable to have a license mandating the use of one of two marks? That is, might you require those who don’t qualify for the “Creator Endorsed” mark to include a mark saying “Not Creator-Endorsed: Proceeds Do Not Support The Artist”? How might that change the equation?

A fascinating conversation; I love reading two intelligent people approaching these thorny issues with maturity.

That said, I have a *big* problem with your stance on trademarks. Wanna know why? Because I lost a product name to someone with more money than me (I’m a software developer). He wasn’t there first, and we weren’t even competing in the same market; it’s just that he could afford to 1) register the trademark and 2) hire a lawyer. I couldn’t. My little toy isn’t even that well-known: it had only one user besides myself, and that one user switched to something else in the mean time. Well, this guy shows up out of nowhere, three years after I launched it, and warns me to change the name or else. To his credit, at least he was unfailingly polite all the way, but that’s little consolation.

And trademarks don’t even help that much after all; manufacturers of pirate consumer electronics, for example, will simply slap a brand name on their product that is far enough from the original to not trigger trademark law, yet close enough to confuse a buyer with poor reading skills, which is all they need. (I’ve seen it happen; it’s an enlightening experience.)

No, trademarks aren’t more justified, let alone better, than the other forms of “intellectual property”. On the contrary, they are the easiest to abuse, and the only form of IP that doesn’t expire. Because, you know, having monopolies wasn’t bad enough; we needed a monopoly that lasts forever.

So meh.

I do believe that there are a couple of things that were meant to be free in the first place.

The first is Culture. Studying the most ancient laws, there was never a law against the copying of Culture except in China when they were printing with wood block, and in Merry Old England when the English Government created copyright.

The problem is Culture was meant to be free in the first place. Checking the most ancient laws, “Thou Shalt Not Steal” and “Thou Shalt Not Bare False Witness” pertained to physical property and identity. There was never a “Though Shalt Not Steal” applied to culture anywhere in the Laws of Hannurabi and the Laws of the Israelites. In fact, Culture in India is considered to be freely taught.

Quite frankly, its as if they were more enlightened than we. The problem is, we think we are better than they, but if you ever look at Hindu friezes on the Hindu temples in Angkor and India, you would see some stark similarities.

Copying does happen, it should happen, and it’s natural to do so. As for trademarks, I’m sorry for what happened to Felix, but Trademarking is a form of branding. Our whole advertising industry depends on Trademarking in order to thrive.

But yes, even Trademark Law needs some sensible reforms.

Elton writes:

“There was never a ‘Though Shalt Not Steal’ applied to culture anywhere in the Laws of Hannurabi and the Laws of the Israelites.”

Unless you’re construing “the Laws of the Israelites” absurdly narrowly, this is not actually true. The Talmud makes a point of the importance of avoiding plagiarism (in the sense of always attributing sources, sometimes with several lines of attribution specifying who one heard it from, who that person heard it from, who that other person heard it from, etc.). There’s also a long history of publishers being granted sole rights to print a given work under Jewish law, under the heading of “hasagat g’vul,” or unfair competition.

What is true, I think, is that the introduction of the printing press changed everything, but that’s a statement that cuts more than one way.

Well, the Talmud was written after the Babylonian Captivity. I was talking about the Torah.

Felt like corey was leading this ‘debate’ throughout the first few tosses.

After that it kinda just died down and started to be another typical… why are we arguing, who cares… type of conclusion.

Re: Elton

“Well, the Talmud was written after the Babylonian Captivity. I was talking about the Torah.”

The Talmud is, of course, generally considered Torah… I assume you mean to restrict this to the Pentateuch, as if that ever existed completely on its own. (In other words, without granting the point, you’ve just confirmed that you’re construing your terms absurdly narrowly.)

It’s a real defeat for human intelligence – monopolies have convinced us that some limited things are unlimited (their annual growth, Earth’s resources), but unlimited things (information, culture, creativity) are actually scarce and exclusive. With that framework in place, they can exploit the naivеte of investors and consumers alike. These investors and consumers become enthusiastic collaborators, as well as zealous defenders of the corrupt status quo. And in the end it’s all about wringing out the maximum amount of money a person can give without ceasing to exist (or more, if you introduce debt to the system).

Cory’s anecdote about how his agent and editor thought he was nuts for suggesting a less restrictive license suggests that an -SA license would protect him from commercial exploitation just as much as an -NC license. For example, NBC Universal would never produce a $100 million unauthorized film adaptation of Little Brother simply because they would never, ever, in their wildest dreams comply with an -SA license.

But the point is Cory wants some commercial exploitation. I think the fear is that under -SA, NBC Universal wouldn’t produce a $100 million authorized adaptation either. Of course the holder of the -SA license can still allow more restrictive uses on a case by case basis; in that way it may offer even more industry deal-making leverage than -NC.

In practicle terms, how would I, a flickr user who publishes many of my photos as a Creative Commons – Attribution v.3 license, instead attach the QuestionCopyright’s Creator Endorsed Mark? I gladly allow blogs to use my photos, but one commercial enterprise was using one of my pictures on thier comercial website, without any attribution for the picture, but attributing the article to their staff writer. I had several email exchanges explaing attribution and the rest of the license before I had to ask them to stop using my photo. Would I still be able to request his refrain under the CE Mark? ANd is there a CE Mark photos websites with facilities to assist publishers/distributers? It seems a bit under-matured for my purposes (I didn’t want to sound condesending by using the phrase immature).

The CE Mark is NOT a license! It’s a mark. Used with a Share-Alike license, it packs a wallop. Used with a more restrictive license, it’s mostly cosmetic.

Every use of the CE Mark needs to be negotiated, just like every use of “rights” does under copyright. It works just like copyright, except without anyone’s freedom being restricted.

A very late comment, but I am curious to what you would say about Schmuels question in a comment above (September 2, 2010 at 9:10 pm):

This may be a stupid question, but would it be possible and/or desirable to have a license mandating the use of one of two marks? That is, might you require those who don’t qualify for the “Creator Endorsed†mark to include a mark saying “Not Creator-Endorsed: Proceeds Do Not Support The Artist� How might that change the equation?

I was thinking exactly the same. Any thoughts?

Two bright people, disagreeing on a thing without anybody behaving like a 6 year old… clearly my internet has been hacked.

(I agree with Nina on this issue, by the way: I despise the “political means” in its every manifestation… and as anybody with a passing knowledge of calculus of variations can tell you, the removal of any false constraint always results in a maximum that is strictly no lower than the constrained solution [higher, for minima]).

Back to the discussion though… I’m confused: internet protocol clearly calls for Hitler to be introduced into any e-mail exchange in which the parties are not in 100% agreement… as in

“Yeah, right. You know who else wanted to enable non-oligopolistic commercialisation of original artwork while simultaneously encouraging artistic diversity? HITLER.”