A Hundred Hundred-and-Fifty Dollar Drawing. Hundred Dollar Drawings are now $150 due to inflation, but still a bargain! Available here.

Category: the interwebs

App-ocalypse

There’s now an APOCALYPSE ANIMATED APP! It lets you store the entire Book of Revelation with almost 300 animated loops on your own device(s). Never again rely on iffy internet for your Apocalypse needs! Engineered by Atul Varma, currently for iPhone only. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/apocalypse-animated/id1610949716

Apocalypse Animated video

I made this little “trailer” video for ApocalypseAnimated.com . It’s only 3 minutes long, while there are almost 12 minutes of animation (without even looping!) in the project, so this is but a mere sample of the wonders to find at the website. But this has music so people are likelier to share and attend to it.

There are some technical looping flaws that bother me. Apparently when I export HD video from Moho, it omits the last frame of the loop, causing a jerk in the seams. This doesn’t happen when I export gifs. To make my hi-res video archive perfect, I will have to go back and add one frame and re-render every. single. file. This took 4 boring tedious days last time, and I’m not looking forward to doing it again. But such are the responsibilities of an Apocalypse animator.

Choosing the song was not straightforward. I was really smitten by Fuck Everything by Euringer (aka Jimmy Urine). It would have supplied nice ironic tension because it’s not intentionally about the Apocalypse, and it’s from the point-of-view of two bratty entitled lovers, which is an interesting lens through which to view John of Patmos and his God. But Fuck Everything already has a perfect video, and who knows what kind of headaches it would cause me; even if Jimmy isn’t a copyright maximalist, his songs are distributed in a system that doesn’t recognize Fair Use, and YouTube’s ContentID would surely block even its first upload. I did start making an edit with it, but got frustrated (as one does) and that anxiety contributed to my consideration of an alternative song.

Fortunately I’d already compiled a list of old gospel songs that might work, and the top entry proved a good fit. I found it on the wonderful archive.org, where I always go a-hunting in my research phases. I worried that straight-up gospel wouldn’t be ironic enough with the animation, but When The Fire Comes Down had its own irony, contrasting a cheerful jaunty melody with horrific subject matter. Everything fit right away and I banged out this edit in a single day. Thank you, Internet Archive!

Heterodorx

Hey TERFs and Trannies! That’s my signature greeting on Heterodorx, the new podcast I’m doing with Corinna Cohn. Our first episode was recorded Friday evening, after I’d biked 30 miles and hiked two, so I wasn’t at my most articulate. We had some technical issues, including my cat, Lola, rubbing her head against my mic, causing loud horrible noises we couldn’t remove due to recording everything on a single track. Our next episode should be better. Still, I like this first foray, and hope you listen.

Heterodorx podcast

Heterodorx web site

Collective Senescence

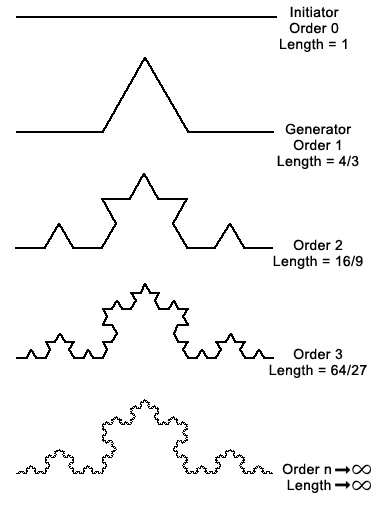

When I learn a new song – something I do unconsciously, every time I am exposed to new music – is some other song erased in my memory to make room? No. I seem to have unlimited capacity for memorizing music, even as my memory is like a sieve elsewhere. How does my brain do that? Does it re-use existing pathways, or create ever-more byzantine new ones? I imagine my mind’s architecture as ever-expanding fractals, filling the same space with more and more curves and crevices.

The older I get, the more byzantine my mind’s labyrinth, all to store the unceasing stream of new information. Now, when I forget the name of something, I imagine the word stuck in a crevice of the fractal. When I was younger and my pathways less intricate, there weren’t enough curves and bends for words to get caught. Now they snag on every corner.

What is information? In my life, it includes experiences. Every day is different; every day impresses new memories. Do the old ones disappear? Certainly my memories are difficult to access, especially names. But I know they’re in there somewhere. I’ve had deeply stored knowledge return to consciousness when revisiting geographical places, homes I’d been in before but never thought about since. If you asked me to recall my friend’s house in San Francisco between visits, I’d have come up blank; but revisiting, I knew where everything was. I took delight in long-buried memories flooding my consciousness as I rode a bus from the airport to the Presidio two years ago. Sometimes that visit felt like walking through my own dreams, geography and symbols shaped by my lifetime of accumulated experience.

Then there is the information of stories, words, music, numbers, images: Culture. Culture is collective, a living thing like a tree or forest that grows in the soil of human minds. Cultural information is experienced through exposure – reading, listening, tasting – and stored in everyone who experiences it.

How many songs will I store in my lifetime? How to even count? Some of them are surely buried too deeply in my mind to recall at will, but they are still there. All that information embedded in our minds’ labyrinths, that we are not aware of, is what Jung called the Collective Subconscious. Like the webs of biological life on this planet, they are too vast and complex for us to comprehend. We are only aware of a tiny bit at a time.

As I age, I find comfort in routine. Every day resembling the next makes memory storage easier. A curve of the fractal is already structured to store much of the day, with only a few details to be slotted elsewhere. Too much information at once can be traumatic. Moving house is traumatic for me, having to learn a new space. Moving to a new region is more so: having to make new friends, locate new food sources, learn new roads. Moving to a new country is more traumatic still, with new regulations, currencies, bureaucracies, and, most daunting of all for an older person, new language. All of these require new memory structures, new tunnels excavated in the catacombs. A young mind, like an “uncarved block,” takes this on with relative ease. An old mind has already been carved to delicate tracery, every branch with more branches, like the fragile intricate lace of an autumn leaf. Carve more into that, and you’ll tear a hole.

Even without trauma, the mere accumulation of experience over time leads, inevitably, to structural collapse. From the outside, this may look like senility. I increasingly believe that senility is an inevitable phase of consciousness. Live long enough, you will develop dementia. At least that’s how it looks from the outside; I don’t know what dementia is like from the inside, although I’ve read some reports from writers in its early stages. Surely some of the “blocks” our experience carves are more robust than others; a crumblier material may suffer early-onset dementia, while the most solid will die of other causes before their veins of memory fractals become too fine to sustain.

But what of our collective mind? We store information collectively too, as Culture. An ever-expanding human population is one way to increase storage capacity. But consider that many of us are storing the same things: the same languages (the number of living languages is decreasing even as the population increases), same songs, same movies, same stories. This is due to media. Literacy/writing was a great early cultural storage invention, allowing far greater numbers to be exposed to the same information. The printing press increased this exposure exponentially. Then phonographs, movies, radio, and television, leading up to, of course, the Internet, the greatest information-exposure system ever created.

Many of us, like me, spend hours a day “scrolling” information online. The density of words, pictures, and sounds is…well, it’s insane. Individually, I am storing this stuff; it’s shaping my neural pathways in ways I don’t know. I may not know exactly what it’s doing, but I know it’s doing something, accelerating the rate of tunneling of my memory labyrinth, increasing the complexity of my mental fractal. If I am wasting my attention on social media, it is because there is a cost: every stupid piece of (mis)information, adds that much complexity to my neural pathways, that much fragility to the overall structure, and brings me that much closer to senility.

Likewise, collectively, we have massively increased our exposure to information. Our collective memory structure, whatever it is, is collectively growing ever-more complex.

Collectively, we are becoming senile.

Complexity is fun (beneficial, desirable) for a while, but eventually and inevitably it leads to collapse. I’m not against complexity; it’s inevitable. Culture is a life form, and all life forms die. There is no way to stop this. Death is a consequence of life; dementia is a consequence of consciousness.

The Internet Is Broken

The Internet is broken,

The Freedom Train has stalled.

The Netizens are woken,

The gardens all are walled.

If anyone’s outspoken,

They soon will be recalled.

The Internet is broken

and I’m sitting here, appalled.

The Internet is busted;

its people are at war.

The principles I trusted

I don’t trust any more.

Our minds are maladjusted,

but we cannot restore

the Internet we busted

to the one we had before.

This song actually has a cheerful melody, but since I can’t write musical notation you’ll just have to trust me on that, until I attempt to record it.