The “European Jew/Zionist” label has has drawn the most criticism in This Land Is Mine. Apparently to Israelis (correct me if I’m wrong – this is what I’m learning from the many comments on the movie, and emails) “Zionist” means “historical Zionist” – the mostly-secular, mostly-socialist, hardworking kibbutz-founding idealists who settled mostly-peacefully in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. According to one correspondent,

the founders of Israel in general were not religious Jews but on the contrary – secular and even anti-religious…The mainstream of ultra-orthodoxy sees Zionism as blasphemy… As for the image – in Israeli culture we have a caricature called “Srulik” (which is a nickname for the name “Israel”) that depicts the stereotypical 1940’s “new Israeli Jew” with the hat and the sandals…

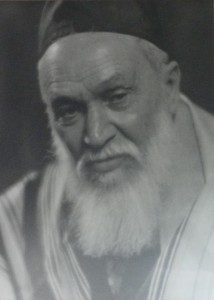

Some viewers seem to think my illustration is a Chasid. It’s not; it’s supposed to be an Orthodox-ish Jew. Orthodox Jews apparently don’t have to join the Israeli army (WTH not?!) so this depiction further bothers some people. Orthodox Jews, they point out, are not Zionists.

Here I must clarify that “Zionist” means something slightly different to me, as an American Jew. Wikipedia sums it up:

Zionism (Hebrew: ×¦×™×•× ×•×ªâ€Ž, Tsiyonut) is a form of nationalism of Jews and Jewish culture that supports a Jewish nation state in territory defined as the Land of Israel.[1] Zionism supports Jews upholding their Jewish identity and opposes the assimilation of Jews into other societies and has advocated the return of Jews to Israel as a means for Jews to be liberated from anti-Semitic discrimination, exclusion, and persecution that has occurred in other societies.[1] Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Zionist movement continues primarily to advocate on behalf of the Jewish stateand address threats to its continued existence and security.

I labelled my Orthodox-ish Jew “Zionist” to distinguish him from Jews who aren’t Zionist – like me. When I was growing up, well-meaning relatives and acquaintances would keep asking me when I was going to Israel. “Why should I go to Israel?” I’d ask. Stricken, they would explain how important Israel should be to me. “Everyone needs a homeland!” they’d insist. But I already had a honemland – Urbana, IL. I felt no need for another one, and was troubled that I should create in myself such a need where one didn’t exist. I had enough insecurities already.

Many people use “Jew” and “Zionist” interchangeably, but they’re not the same thing. I am a Jew because I’m descended from a long line of Jews, and because even as atheists my family retained some Jewish cultural quirks. But I am not a Zionist. I don’t need a “homeland” in Israel, and I don’t care if my “Jewish identity” is upheld and assimilation resisted; in fact assimilation is part of my “Jewish identity,” something I’m proud of (as much as I can be legitimately proud of anything other people did before I was born).

I realize as I write this that I represent the religious conservative’s worst nightmare. Like most religions, Judaism requires indoctrination at an early age; Orthodox and Chasids encourage breeding as many offspring as possible, to enlarge the tribe. Assimilation is anathema to religious Jews, because it leads to people like me. I’m supposed to be supporting the Tribe, and instead I’d rather make graven images and spout individualism. I’ve even refused to breed altogether, let alone indoctrinate any spawn.

Anyway, my Orthodox-ish Jew character, if he’s in Israel, is what I’d call a Zionist, although most Israelis would not. That said, I could have left the confusing Zionist label off of him, because he obviously was in Israel in my cartoon.

The “European” part of the label refers to the pressure a vast influx of Jewish refugees from Europe put on Palestine. Yes, there were Zionists there already, living peacefully alongside Arabs and others in the region. And yes, the State of Israel welcomes (or is supposed to welcome) all Jews, not just European ones. But the post-war influx of European Jews really changed things in the region. Would the State of Israel have been established had that not occurred? Would the US have backed it otherwise?

Why did I draw my character Orthodox-ish at all, when most Zionists and Jews and Israelis don’t look like that? To show the religious side of a “Jewish nation-state” (remember it’s the Jewish nation-state idea that defines Zionists here in the U.S.) And to refer to what I consider the most problematic element in Israel and elsewhere: religious nuts. My character doesn’t look too different from these folks hanging out at the Wailing Wall:

Sayeth Wikipedia:

With the rise of the Zionist movement in the early 20th century, the wall became a source of friction between the Jewish community and the Muslim religious leadership, who were worried that the wall was being used to further Jewish nationalistic claims to the Temple Mount and Jerusalem.

Then of course you have “The Settlers“:

I chose the more Orthodox garb because to me it more than anything said, “religion.” But critics do have a point when they say the Orthodox Jews in Israel get others to do their shooting for them.

I chose the more Orthodox garb because to me it more than anything said, “religion.” But critics do have a point when they say the Orthodox Jews in Israel get others to do their shooting for them.

There are Jews who are not Zionists. There are Zionists who are not Jews. Most Jews are not Israelis; most Israelis are Jews. Many Jews are not religious; many Israelis are not religious. There are deeply religious people who aren’t violent. There are violent people who aren’t deeply religious.

But when you combine religion, cultural identity, and statehood, you get a bigger mess than any of those things alone. My Orthox-ish dude is contemporary to his State counterpart:

(Thanks to another group of comments, I now know he’s holding the wrong kind of gun, and he’s holding it wrong. That I can live with.)