Sita Sing the Blues has a few Endorsed DVD distributors. In addition to QuestionCopyright.org and myself, there’s FilmKaravan, a distribution collective that handles “downstream” deals with VistaIndia and IndiePix. Their distributions are on amazon.com (I get a much smaller percentage from those than from my DVDs, but they reach a much wider market) and Netflix.

In addition to physical DVD rentals, Netflix offers subscribers instant electronic delivery: streaming movies over the Internet to Mac, PC, Wii, PS3 and Xbox players. Many subscribers conveniently find new titles through this service. It’s just the sort of distribution channel that benefits a small film like Sita. They also pay producers, and don’t demand exclusivity. It’s a good deal all around, except for one problem: DRM.

DRM, or Digital Restrictions Management, is technology “to control use of digital media by preventing access, copying or conversion to other formats by end users.” At best DRM reduces the functionality of computers; at worst it invades privacy and adds surveillance and malware. DRM End User License Agreements (EULAs) force users to surrender rights well beyond what copyright restricts.

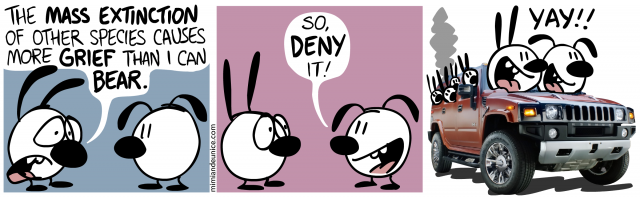

In the last few years DRM has grown increasingly pervasive, with little-to-no press coverage. Consumers passively accept it, as proven by Apple’s new “everything-DRM” device, the iPad.

Creators, too, are accepting DRM as a fact of media distribution; offered no alternatives, they lose their ability to even imagine alternatives. DRM, like rights monopolies, is said to be made for creators. But like copyright, DRM is designed to benefit Big Media conglomerates, not artists.

If this type of invasion of privacy were coming from any other source, it would not be tolerated. That it is the media and technology companies leading the way, does not make it benign. (link)

A few weeks ago a content aggregator called Victory Multimedia contacted FilmKaravan:

Netflix has shown interest in carrying your title “Sita Sings the Blues” for Electronic Delivery. For a 12 month license period they are offering $4,620.00. You would received $2310.00 no later than 60 days after the Netflix title release date and the balance of $2310.00 will be paid 6 months after the initial payment.

First I asked (Filmkaravan to ask the aggregator to ask Netflix) if Netflix could make a DRM exception for Sita. Unfortunately no such option currently exists in Netflix’s electronic delivery system. Possibly no other filmmakers have even asked for such an option. iTunes used to offer only DRM music, but eventually enough people – including savvy “content providers”? – demanded DRM-free channels that they now offer DRM-free music for sale along with Defective options (all iTunes movies carry DRM). Filmmakers lag far beyond musicians in understanding the Internet, so it may be a while before Netflix, Amazon, iTunes, and other online distributors allow our “content” in their channels without adding malware and spyware to our films.

I still wanted Sita to be in Netflix’s on-demand system. I want as many people to see Sita as possible; surely many viewers now rely on such a convenient delivery system to explore new films. Anyone who became a fan of Sita this way might still find the film’s web site, and learn how to download a free copy for themselves. Although Sita’s site states:

You are not free to copy-restrict (“copyright”) or attach Digital Restrictions Management (DRM) to Sita Sings the Blues or its derivative works.

I could still grant special permission to Netflix to add DRM to Sita. I asked if I could add a card to the front of the movie stating simply:

Download and share this film from:

sitasingstheblues.com

The aggregator responded this was not possible, due to a Netflix “no bumpers” policy.

Looking back, I was conflicted because it was hard for me to see the DRM on Netflix’s streaming service as problematic. It’s not as though Netflix is telling anyone they’re “buying” the movies they stream; they’re just “renting” them. “Rental” already implies restrictions and limited use terms. They’re just trying to make the Internet work like the physical world, imposing artificial scarcities to resemble the natural scarcities of physical DVD rentals. We can accept natural scarcities; why not accept artificial ones?

I was so conflicted, I asked my “Facebook friends” for advice. Responses were pretty split. Only a few knew what DRM was, but understood I could be compromising my principles by endorsing its use. Was that compromise significant? Was it time to “rise above my principles”?

Facebook, being a walled garden whose “business model is spying,” is problematic itself; obviously I use it anyway, although I don’t expect it to be around in a few years unless it opens up. Two of my moral guidestars don’t use it out of principle, and I emailed them for advice. Richard Stallman wrote,

I faced the same sort of question today: whether to approve release of my biuography with DRM for the iBad. I said no, because the fight against DRM is my cause, and the iBad is the most extreme attack against computer users’ freedom today.

It is self-defeating to try to promote a cause by supporting a direct attack against it. Lesser forms of participation in things that you hope to eliminate can be overlooked, but Netflix is something we must specifically fight. The example you would set by giving in would undermine everything….

We launched an action against Netflix. We tell people, “Don’t be customers of Netflix.”

So I learned Netflix DRM was “real” DRM, rental or not. DefectiveByDesign.org asks people who rent physical DVDs from Netflix, to protest their DRM-laden electronic delivery service.

It was John Gilmore’s email that hit me where I live:

Don’t post your film via a DRM service.

Insist that Netflix is free to release it without DRM, but they cannot release it with DRM.

Creators keep knuckling under to these media middlemen who push DRM onto end users for their own lock-in reasons. Like Apple. Like CDbaby.

It will take pushback from creators to change this. Be the change that you want to see….

I’ve been the “change I want to see” in regards to copyright monopolies. People told me I’d lose everything by copylefting Sita, including all hope of professional distribution. But in fact, some professional distributors became willing to distribute Sita without claiming monopolies over it, and we’re all fine.

I’d still love Sita to be offered through Netflix’s online channels; if they ever offer DRM-free video-on-demand, I hope they remember Sita Sings the Blues.

For now, people will just have to obtain Sita by visiting the vast big Internet outside of Netflix. Most of the Internet still isn’t enclosed by Netflix, or Amazon, or iTunes. Most of the Internet is still Free; I’m doing what little I can to keep it that way. I’m sad to lose the potential viewers who may have found Sita through Netflix’s electronic delivery. But maybe some of those Netflix subscribers will discover the rest of the Internet because of my tiny act of resisting DRM.