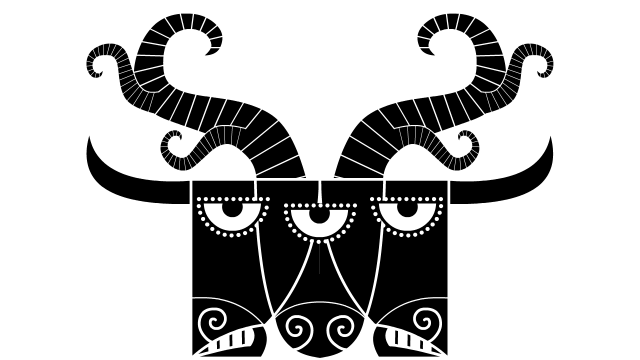

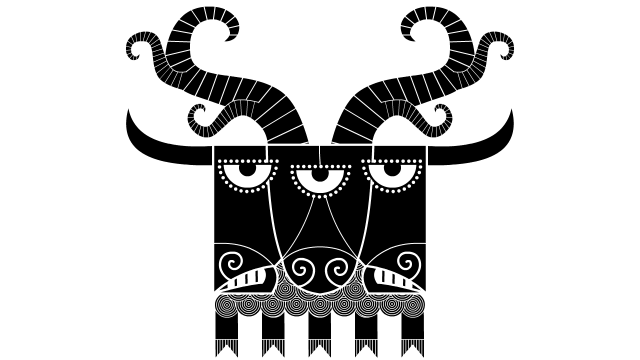

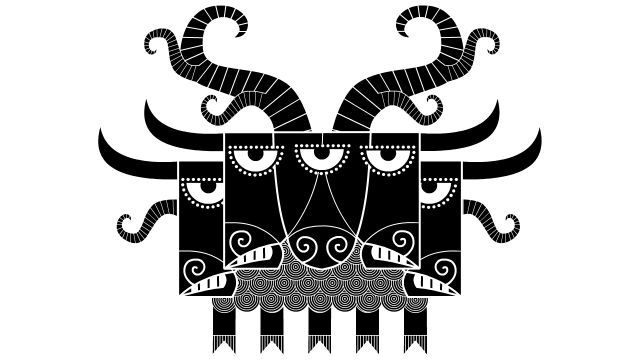

Some infinities are bigger than others. This Leviathan has a few extra receding loops, making it more infinite than the version I posted earlier.

Some infinities are bigger than others. This Leviathan has a few extra receding loops, making it more infinite than the version I posted earlier.

Leviathinfinity

The Stomping Behemoth

Behemoth Finalists

Now with bodies! No matter what I did, the Muse kept guiding me toward symmetry, especially adding the body. Yes it has 5 legs, like a Shedu. Yes it looks like a sheep. A powerful, gigantic, terrifying monster sheep. I still haven’t decided whether it will have 3 faces or 5.

Choose your favorite Behemoth

Leviathan

I designed this Leviathan for my upcoming Seder-Masochism project (new website coming soon). Jewish mythology doesn’t have a lot of visual representations of monsters. Lions, grapes, and decalogues, sure, but not monsters. The Big Three are Leviathan (the sea monster), Behemoth (the land monster), and Ziz (the air monster), all of which are KOSHER!