Working on a cat to eat the goat. No, cats don’t eat goats, but that’s what it says in the song.

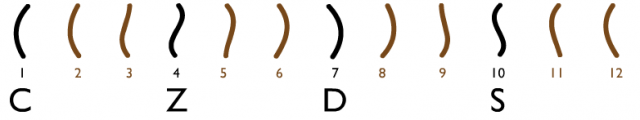

Waves and Locomotion

Most natural movements – runs, walks, gallops – follow wave patterns. But it’s very difficult for me to analyze such movements so I can recreate them in animation.

For this experiment I worked backwards, first creating the simple wave movements (above) and then combining them into a gallop (below).

For this experiment I worked backwards, first creating the simple wave movements (above) and then combining them into a gallop (below).

The legs are swinging back and forth as well as waving.

One Little Goat

Davis Vertical Feed restoration

Blogger’s Quilt Festival – “Ziz” quiltimation in Art Quilts

Approximately 32″ square. Cotton fabric, cotton/bamboo batting, rayon thread. Machine embroidery, quilting, trapplique.

I’m submitting this in Art Quilts because there’s no “animation” category in the Blogger’s Quilt Festival. 😉 I’m happy to have it in an online show, because you can easily see it animated:

Each block of the quilt is a frame in the animated cycle above. I created the animation, exported as vector images which Theo Gray stitchcoded in Mathematica. Each block was stitched in 2 parts on our embroidery machine: first the Ziz (gryphon) figure, then the background. I cut out and applied the former to the latter and the machine “trappliqued” it down and did the echo pattern. Finally I zigzag stitched the blocks together, topstitched homemade bias tape over the seams, and bound it.

Each block of the quilt is a frame in the animated cycle above. I created the animation, exported as vector images which Theo Gray stitchcoded in Mathematica. Each block was stitched in 2 parts on our embroidery machine: first the Ziz (gryphon) figure, then the background. I cut out and applied the former to the latter and the machine “trappliqued” it down and did the echo pattern. Finally I zigzag stitched the blocks together, topstitched homemade bias tape over the seams, and bound it.

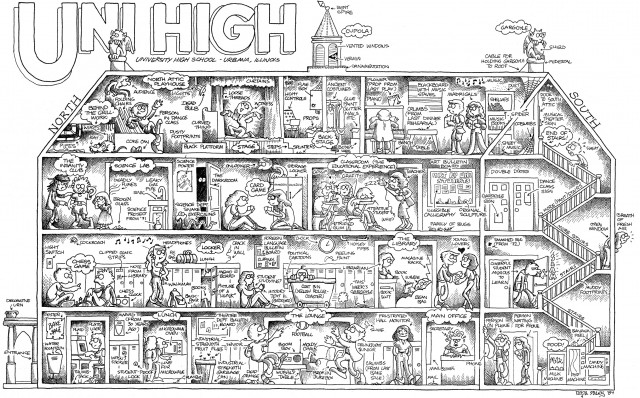

Alumnuts

Super high-res (800 dpi) image at archive.org!

I recently dug up, scanned and restored this cartoon I drew in 1984 for the Uni High yearbook. It makes me nostalgic not for school (for which I still carry much resentment*) but for the glorious escape drawing provided those years. There were no art classes at Uni while I was there, for which I am eternally grateful. While my liberal friends are mostly “arts education” boosters, I owe my survival to Art staying beyond the reach of school, teachers, and institutionalization. School ruined math, literature, physical exercise, social interactions, and pretty much everything else that could be beautiful – thank doG it didn’t ruin drawing too.

*Dropping out of the University of Illinois at the end of my Sophomore year was the first Great Decision I ever made. My second Great Decision was freeing Sita Sings the Blues and dropping out of Copyright. I’ve only made two Great Decisions in my life, but they’re plenty. Dayenu.