I have no desire to animate. Add my work to a media stream already full of fascinating hallucinations? The creativity of AI exceeds my own, with its innumerable fingers and multiple arms and morphing cat heads. Things turning into other things used to be magic worthy of hard work and years of study. Now it’s a mere artifact, a waste product generated in pursuit of the more mundane.

All my work will be forgotten, because there is so much work. Art used to be diamonds the future could sift from the dust. Now the dust is made of diamonds. I used to imagine I was making Art for the Future, but no future will find mine. I guess it’s just for me, and a small audience of the Present, and God. That’s enough, but it’s humbling. A glove has no more or less value than a feature film.

I thought Sita was future-proof because of Free Culture, but that only protected against Copyright. Cancel Culture was still to come, and there’s no protection against that except cowardice, which kills art before it’s born. And now the glut of “content” is on steroids. Attention is fractured and overwhelmed. Anything I make is buried in diamonds.

Still, I make, like writing this now. Like the countless un-named and un-indexed photos I take on my bike rides, not even worthy of my own efforts to organize. I make little posts on social media to be forgotten by the next day or, at best, next week. I chatter to my fellow monkeys, amidst the chatter of robots, as if monkeys are so starved for chatter we have to build robots to do it for us.

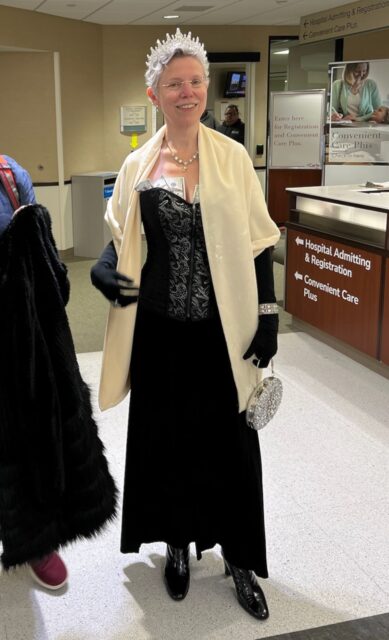

Yesterday at my women’s meetup M and L brought knitting. M finished a blanket she’d worked on since 2023. Every row was a different color yarn, to represent the high temperature of that day, 365 rows total. It has no commercial value. It represents countless hours of work. It will be used only by M, and seen only by a few of her friends (like us). It is Art. It will be forgotten like all art, and like all of us. We are here today only. That has to be enough.